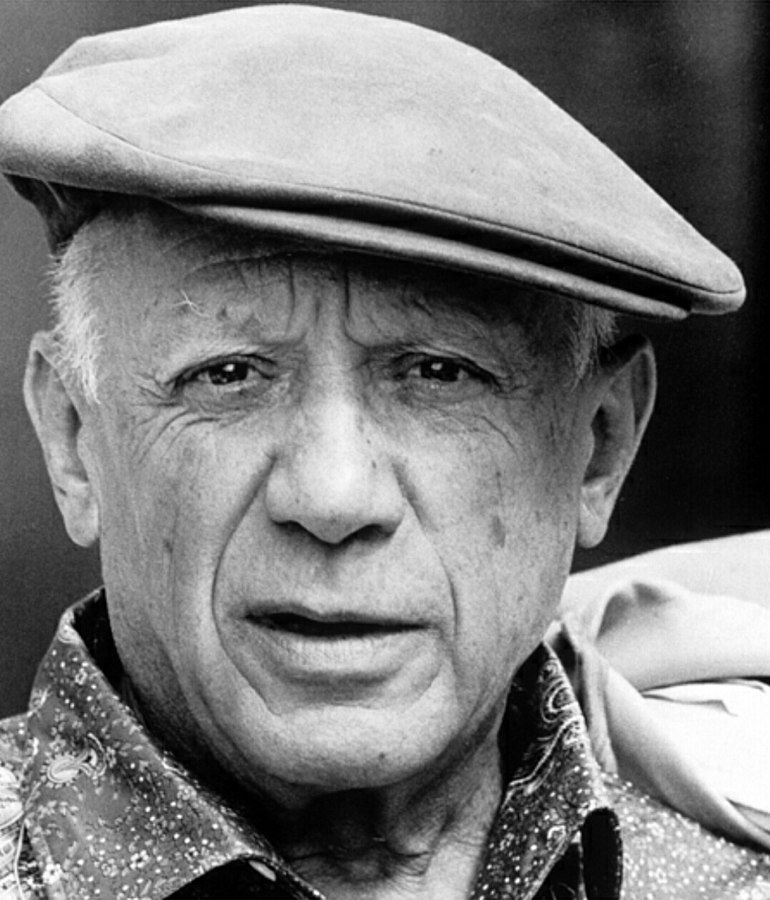

Pablo Picasso, Content Creator

Hey all. Let’s hop to it.

Recent Appearances

I was just a guest on American Prestige and rambled a bit, prompted by the end of Succession, about the role of media in politics. I was also a panelist at an interesting symposium Catholic University hosted a couple of weeks ago on beauty. You can watch my remarks on beauty and democracy here. I might publish them in the newsletter soon, so I suppose you could just wait for that as well.

Culture

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death and a number of exhibitions around the world are taking stock of his work and legacy. The most talked about thus far has been “It’s Pablo-matic,” a comic and critical assessment of the man and his myth at the Brooklyn Museum by the Australian comic Hannah Gadsby. I’m not one of the people taking a whack at the thing from a pre-formed opinion on Gadsby themselves; I never got around to watching their specials. But the reviews of the exhibition have been generally bad, including Jason Farago’s scathing and instantly infamous broadside in the The New York Times:

So far as it has an argument — a problematic — it goes like this: Pablo Picasso was an important artist. He was also something of a jerk around women. And women are more than “goddesses or doormats,” as Picasso brutally had it; women, too, have stories to tell. I wish there was more to inform you of, but that’s really about the size of it. All the feminist scholarship of the last 50 years — about repressed desire, about phallic instability, or even just about the lives of the women Picasso loved — is put to one side, in favor of what really matters: your feelings. “Admiration and anger can coexist,” a text at the show’s entrance reassures us.

That Picasso, probably the most written about painter in history, was both a great artist and a not-so-great guy is so far from being news as to qualify as climate. What matters is what you do with that friction, and “It’s Pablo-matic” does not do much. For a start, it doesn’t assemble many things to look at. The actual number of paintings by Picasso here is just eight. Seven were borrowed from the Musée Picasso in Paris, which has been supporting shows worldwide for this anniversary; one belongs to the Brooklyn Museum; none is first-rate. There are no other institutional loans besides a few prints brought over the river from MoMA. What you will see here by Picasso are mostly modest etchings, and even these barely display his stylistic breadth; more than two dozen sheets come from a single portfolio, the neoclassical Vollard Suite of the 1930s.

[...] A more serious look at reputation and male genius might have introduced a work by at least one female Cubist: perhaps Alice Bailly, or Marie Vassilieff, or Alice Halicka, or Marie Laurencin, or Jeanne Rij-Rousseau, or María Blanchard, or even Australia’s own Anne Dangar.

Instead, “It’s Pablo-matic” contents itself to stir in works by women from the Brooklyn Museum collection. These seem to have been selected more or less at random, and include a lithograph by Käthe Kollwitz, a photograph by Ana Mendieta, an assemblage by Betye Saar, and Dara Birnbaum’s “Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman,” a video art classic of 1978/79 whose connection to Picasso is beyond me. (At least two paintings here, by Nina Chanel Abney and Mickalene Thomas, draw on the example of Manet, not Picasso.) The artists who made them have been reduced here, in what may be this show’s only true insult, into mere raconteurs of women’s lives. “I want my story to be heard,” reads a quotation from Gadsby in the last gallery; the same label lauds the “entirely new stories” of a new generation.

Reducing women to their personal narratives, Farago goes on to say, reduces the significance of their formal accomplishments and talents, and a more meaningfully provocative exhibition might have placed them in real conversation with — or elevated them above — Picasso and his work. “Howardena Pindell, on view here, is much more than a storyteller; Cindy Sherman, on view here, is much more than a storyteller,” he concludes. “They are artists who, like Picasso before them, put ideas and images into productive tension, with no reassurance of closure or comfort. The function of a public museum (or at least it should be) is to present to all of us these women’s full aesthetic achievements; there is also room for story hour, in the children’s wing.”

Some of the backlash to the Gadsby backlash mirrors the exhibition itself in this way. It’s true that Gadsby, one of the few visible gender non-conforming people in comedy today, is making this provocation at some personal and professional risk, but that’s no reason not to critique the substance of the exhibition or to evaluate whether the provocation succeeds on its own terms; Farago makes a good case that it doesn’t. “[W]ho should be most brassed off by this show?” he asks. “Not Picasso, who gets out totally unharmed. But the women artists in the museum’s collection dragooned into this minor prank, and the generations of women and feminist art historians — Rosalind Krauss, Anne Wagner, Mary Ann Caws, hundreds more — who have devoted their careers to thinking seriously about modern art and gender. Especially at the Brooklyn Museum, whose engagement with feminist art is unique in New York, I left sad and embarrassed that this show doesn’t even try to do what it promises: put women artists on equal footing with the big guy.”

While the review is being framed in some corners as personal attack on Gadsby, the mode of cultural analysis and commentary it describes and decries is quite common now; Gadsby is hardly the only cultural voice these days implying that aesthetic questions should generally take a backseat to context and “content,” — that now inescapable word we apply to both the subjects of art and the position art occupies in culture today, as grist for an always running discursive mill. The formal properties of visual art, music, and literature interest people who talk actively about art far less now than how artworks might function as signifiers or symbols and how they might reflect the cultural standing, politics, or personal ethics of their creators and consumers.

I recently revisited Susan Sontag’s classic 1966 essay “Against Interpretation” with all of this in mind. Her general argument is that trying to figure out what a work of art is “really about” or to probe all that might lie beneath its surface can wind up smothering art and flattening our experiences of it. Overanalysis, she contends, can cut off our access to the sensory and aesthetic properties of a work in itself and the thoughts and emotions it might directly provoke — all to make art more useful to some other end. “Interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art,” she wrote. “It makes art into an article for use, for arrangement into a mental scheme of categories.”

I’ve never been particularly taken with this essay, truth be told; for starters, there’s a lot of argument by assertion going on. We’re told, for instance, that the real import of the surreal and dreamlike images in Alain Resnais’ Last Year At Marienbad lies not in whatever symbolic and allegorical meanings they might hold but their “pure, untranslatable, sensuous immediacy”; the film is significant, Sontag contends, for its “rigorous if narrow solutions to certain problems of cinematic form.” Well, who says and why? In general, I think that writing off most of the matters that critics contend with completely— latent conscious or unconscious meanings, historical, cultural, and biographical context, and so on — and disdaining art and artists that have “something to say,” as Sontag does, would shrink and constrain our sense of what art can do and limit our understanding of the role it plays in our lives and the world around us.

But as underdeveloped as I find “Against Interpretation” in places, there’s something undeniably refreshing about reading it today at a time when culture and commentary about it have been given over so completely and uncritically to the interpretive dynamics Sontag warned about — at a time when we’re being overwhelmed, again, by “content” in every sense:

Interpretation takes the sensory experience of the work of art for granted, and proceeds from there. This cannot be taken for granted, now. Think of the sheer multiplication of works of art available to every one of us, superadded to the conflicting tastes and odors and sights of the urban environment that bombard our senses. Ours is a culture based on excess, on overproduction; the result is a steady loss of sharpness in our sensory experience. All the conditions of modem life-its material plenitude, its sheer crowdedness-conjoin to dull our sensory faculties. And it is in the light of the condition of our senses, our capacities (rather than those of another age), that the task of the critic must be assessed. What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more. Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all.

Cultural progressives have a tendency to regard the focus on aesthetics Sontag calls for as intrinsically conservative or reactionary, and I think wariness about the politics of elevating form over meaning and context is defensible. Elites on the right have always droned on and on about protecting beauty and the sublime from the degeneracy of cultural radicals; this realm of cultural critique has itself degenerated in recent years into philistine sloganeering and memery from marble bust accounts. We shouldn’t take our inherited standards of beauty for granted or the notion that beauty ought to be paramount in art in the first place as a given. The oppression and exclusion that have shaped the aesthetics of Western art and hindered the marginalized from participating in it matter; it matters that Pablo Picasso was not just an asshole but an abusive misogynist whose personal life reflects the challenges women have faced as artists and in art’s cultural spaces. All of this should go without saying.

But it should also go without saying that aesthetics also matter and that the ranks of those who have a vested interest in insisting they don’t, as I’ve written before, now include major corporations that are hard at work pressing as much of culture as they can into a profitable gray slurry. And they benefit from another negative aspect of interpretation as a mass cultural practice that I don’t think Sontag quite foresaw. The idea that most of what really matters about a work of art lies either beneath its surface or outside itself facilitates the project of churning out ready-made bullshit; Ant-Man 13 or some such is a less offensive prospect in a culture always ready to convince itself that a work of art might be more interesting, complex, or worthy of discussion than it initially appears — that the formal properties and accomplishments (or lack thereof) of a work in itself are dwarfed in significance by the meanings we might strain to find within it or the sociocultural conversations we might freight it with.

The truth is that as rigorous as interpretation can be, it’s not especially difficult to whet the interest or satisfy the demands of most of our interpreters. After all, you need little more than an internet connection and a social media account to do the work of interpretation for a mass audience today; though it’s hardly their fault, The Walt Disney Company benefits from the proliferation of interpreters who haven’t seen or experienced enough to know that an individual work of shlock isn’t actually made less schlocky, on formal grounds, by its narrative interconnectedness with twenty-five other works of schlock, or by what one might write about superheroes as mythological figures and archetypes. It’s also not that hard, though conservatives are doing their best to make it harder, for these companies to pump out work that’s scrupulously unproblem- and unPablo-matic. Part of what’s angering the right so these days is that the entertainment industry has taken readily to acts of progressive posturing that cost it relatively little and don’t require much improvement in the actual quality of the work Hollywood puts out. Executives know that most in marginalized groups desperate to finally “be seen” on screen will settle for being seen in something mediocre if need be rather in than something formally novel, challenging, or interesting.

The putatively surface-level questions of aesthetics matter at the level of production as well; the formal qualities of a work, obviously, materially reflect how and why it was made. Three recent pieces on this are worth your time. The first is a review of two new books on Spotify and the streaming music economy by Daniel Cohen in the London Review of Books. As I believe I’ve written here before, the shape of popular music is perceptibly changing in response to technological shifts and incentive structures that remain opaque to most listeners:

If an artist can’t hold someone’s attention for those first thirty seconds, they don’t get paid. Some have adapted the way they go about making music accordingly. In 2010, less than 20 per cent of number one songs in the US had choruses that started within the first fifteen seconds; by 2018, almost 40 per cent did. Meanwhile, hits have got shorter: between 2013 and 2018, the length of the average song on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the US fell from 3 minutes 50 seconds to 3 minutes 30 seconds. (The rise of TikTok, where only a segment of a song tends to be played, has intensified this trend.) Since an artist is paid the same amount irrespective of a song’s length, it makes sense to keep it short, in the hope that a listener will get through more songs. So as pop songs got shorter, albums got longer: between 2013 and 2018, the average duration of the most streamed albums on Spotify increased by almost ten minutes, to sixty minutes. (There have been some endearing efforts to exploit the thirty-second rule: in 2014, the American funk band Vulfpeck released Sleepify, an album consisting of ten silent songs that each lasted 31 or 32 seconds, in order to earn enough money to fund a tour. They made almost $20,000 before Spotify took the album down.)

The second piece — also about sound, really — is Devin Gordon’s bewildered investigation into the popularity of watching things with subtitles in The Atlantic. As it turns out, one of the culprits here, according to Game of Thrones sound mixer Onnalee Blank, is media consolidation:

Specifically, it has everything to do with LKFS, which stands for “Loudness, K-weighted, relative to full scale” and which, for the sake of simplicity, is a unit for measuring loudness. Traditionally it’s been anchored to the dialogue. For years, going back to the golden age of broadcast television and into the pay-cable era, audio engineers had to deliver sound levels within an industry-standard LKFS, or their work would get kicked back to them. That all changed when streaming companies seized control of the industry, a period of time that rather neatly matches Game of Thrones’ run on HBO. According to Blank, Game of Thrones sounded fantastic for years, and she’s got the Emmys to prove it. Then, in 2018, just prior to the show’s final season, AT&T bought HBO’s parent company and overlaid its own uniform loudness spec, which was flatter and simpler to scale across a large library of content. But it was also, crucially, un-anchored to the dialogue.

“So instead of this algorithm analyzing the loudness of the dialogue coming out of people’s mouths,” Blank explained to me, “it analyzes the whole show as loudness. So if you have a loud music cue, that’s gonna be your loud point. And then, when the dialogue comes, you can’t hear it.” Blank remembers noticing the difference from the moment AT&T took the reins at Time Warner; overnight, she said, HBO’s sound went from best-in-class to worst. During the last season of Game of Thrones, she said, “we had to beg [AT&T] to keep our old spec every single time we delivered an episode.” (Because AT&T spun off HBO’s parent company in 2022, a spokesperson for AT&T said they weren’t able to comment on the matter.)

Netflix still uses a dialogue-anchor spec, she said, which is why shows on Netflix sound (to her) noticeably crisper and clearer: “If you watch a Netflix show now and then immediately you turn on an HBO show, you’re gonna have to raise your volume.” Amazon Prime Video’s spec, meanwhile, “is pretty gnarly.” But what really galls her about Amazon is its new “dialogue boost” function, which viewers can select to “increase the volume of dialogue relative to background music and effects.” In other words, she said, it purports to fix a problem of Amazon’s own creation. Instead, she suggested, “why don’t you just air it the way we mixed it?”

Lastly, Malcolm Harris recently assessed the link between formal approaches to special effects and structural shifts in the film industry in a review of a new book on Industrial Light & Magic for The Nation:

The production of Star Wars was inauspicious—over budget and behind schedule—and few expected it to become the cultural phenomenon it became. But whether it was the clichéd narrative, the fun robots, the Freudian subtext, or just Harrison Ford and Darth Vader, Star Wars pumped America’s pleasure centers full of proton torpedoes. Part of the appeal was found in its effects style—futuristic but retro and gritty. Developed by the ad hoc team that became Industrial Light & Magic, this new style of special effects took the film industry by storm. Lucas’s “effects team created a composite mise-en-scène,” Turnock writes, “that combined the New Hollywood cinematographic aesthetic with the flexibility of animation (often drawing from experimental animation) to create a historically determined style of photorealism that aligned with 1970s cinematographic styles.” This combination wasn’t just successful; it was the original sin of today’s special effects, with corporate culture and counterculture merging into one.

Working at a time when “cool” meant “rough”—think handheld shaky cameras and natural lighting—the Star Wars team found an innovative approach to sci-fi. Their “motion-control” camera rigs allowed Lucas to digitally program shots for perfect repetition, which allowed him to compose sequences out of independently filmed elements with relative ease. This was a major advance over special effects teams just trying their best, but it also entailed a smoothness that was out of style. And so coupled with this new smoothness was a purposeful roughness: The aesthetic of Star Wars was not to replicate reality but to recognize the rough-and-ready way that films imitated it. The Star Wars synthesis meant mussing up the cutting-edge effects, lest an outer-space dogfight look too serenely artificial. Lucas and his team developed this into a renegade style that Turnock convincingly compares to that of the so-called New Hollywood classics Badlands and Easy Rider. One hazy, contemplative evening landscape shot of Luke Skywalker on Tatooine is almost identical to a shot from Badlands that Turnock reproduces, except that Tatooine has two suns.

[...T]he Empire of Effects shows how today’s return to pre-CGI effects is part of a longer history—one defined by a realism that never wanted to appear truly real. Against the floaty Yoda of Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith, the new ILM aesthetic is gravity-bound, even if the characters do spend a lot of time flying around. Picking up on Favreau’s rhetoric, Turnock calls this formula “grounded” realism, both because the elements are expected to conform to gravity and because the digital effects are grounded in their practical predecessors. The approach, “modeled on ILM’s 1980s style of highlighting the effect of the human camera operator’s mistakes,” Turnock writes, “is designed to provide that analog feeling to a largely CGI production.” The unconscious nostalgic gestures of the ’80s and ’90s were combined with the conscious nostalgic commercial program of the 2010s to produce a field of Disney content that openly aspires to visual and emotional regression rather than experimentation, adventure, or progress.

Special effects-intensive films and shows are now, in a sense, faking fakery — using puppets in the Star Wars case though they have the means to move beyond them — in order to hook audiences more deeply on their nostalgia. But these productions are still highly dependent on new technologies and the workers who use them in practice, and those workers, the charms of Baby Yoda aside, are being asked to do more with computer graphics than increasingly challenging structural conditions — “decentralized production, inflexible deadlines, and micromanaging so severe that industry professionals call it “pixel-fucking” — really allow. We see the results of that on screen — bad CGI that might get set aside and ignored by critics and consumers more interested in takes about what a film or show is ostensibly doing socioculturally-speaking or in the service of some wider IP strategy.

Even within pop culture at its supposed best, novel form has been supplanted by formula — reliably pristine aesthetic approaches that don’t inspire much critique or analysis from critics and that are actually aimed at giving mediocrity a respectable sheen. “Over time,” Josef Adalian and Lane Brown recently wrote in a piece on the state of the streaming business for New York Magazine, “the expensive signifiers of prestige TV — the movie stars, the set pieces, the cinematography — became so familiar and easy to appropriate that it could take viewers six or seven hours to realize the show they were watching was a fugazi.” And even when the shows are actually good, the commentary around them has gotten rather stilted and formally unmoored, as The Ringer’s Brian Phillips observes in a recent piece on the end of Succession:

Talking about “prestige TV” rather than good TV became a way to take the thorny question of aesthetic value out of the conversation. It was a way to sidestep difficult political discussions about representation and genre and how we distribute cultural spoils. But the faint derisiveness of the term also seemed to mark its user as more in the know, hipper, less naive about human motives. It was a way to talk about art that showed you weren’t enough of a sap to think art was really the goal. It showed you understood that the only things people really care about are gossip and money.

And I think that’s why I feel a little queasy about the term “prestige TV.” It seems to contain its own quiet cynicism. It’s so dismissive of the artistic potential of the medium of television, something I’d very much like writers and showrunners to go on believing in. “Prestige TV” is a phrase that could have sprung from the world of Succession itself (though I’m sure Roman would have called it, like, “sorry fucking national critics circle jerk, founding myth of America’s suburban angst and bison skulls whatever—I don’t care”). It implies that artistic value, like all abstract value, is bullshit; what really matters is status and power. This is not what I believe, and if it was, I’m not sure why I’d ever want to watch television. To live tweet it, I guess?

The collapse of the prestige TV economy seems to be setting up an overcorrection in the industry akin to what took place in the film business during the 1980s in the aftermath of New Hollywood’s revolution, Adalian and Brown write, ”when creativity was suffocated under corporate micromanaging and the rise of tentpole franchises.” “Recently, TV studios have embraced preexisting intellectual property with a cravenness that would shame even the movie industry of the 2010s,” they continue. “Warner Bros. has announced plans to adapt the dregs of the Harry Potter books into a decade-long TV show. Lionsgate says it’s doing the same with the Twilight books. Showtime is developing three Dexter spinoffs, four Billions offshoots, and sequels to Weeds and Nurse Jackie.” All this is happening within an industry that now thinks so little of those who actually do the work of art that even its highest and most revered practitioners might have their specific roles elided and find themselves referred to, flatly, as “creators.”

Much of the above amounts to the take you might expect from a left-wing journalist on why form matters; maybe the act of critiquing and assessing form with an eye to understanding the economic factors and forces that produce it hews too closely to interpretation by Sontag’s standards. But I disagree, again, that interpretation is something we ought to be intrinsically wary of. The problem, I think is that we’ve invested ourselves in modes of interpretation and in a separation between form and content that allow content — both “within” works of art and foisted upon them — to fully smother formal questions. We can do better.

Incidentally, Jason Farago is one of the finest popular interpreters around; his contributions to the Close Read series at the Times really excel at demonstrating how close attention to style can reveal much of the substance we’re now culturally invested in. You come away from those pieces looking at art and the world around us with different eyes. And that, I think, is what criticism is all about.

A Song

“Pablo Picasso” — The Modern Lovers (1976)

Bye.

Nwanevu. Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.